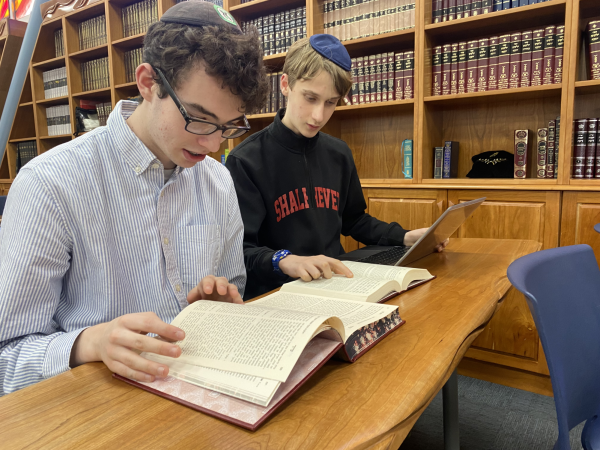

SUMMER OF WAR: Jewish law, though sparse, leans toward self-defense and guarding of innocents

DEFENSE: Iron Dome missiles intercepting rockets sent by Hamas toward Israeli population centers. According to jpost.com, Iron Dome shot down 735 missiles of 3,659 that were fired.

September 19, 2014

From its earliest days, the state of Israel has operated with the spirit of Jewish ethics in mind. But what about Jewish law? Is halacha even appropriate to defend military actions? Can Jewish law provide a legitimate explanation or justification for the killing of civilians in a time of war?

Interviews with rabbis and faculty revealed a diversity of opinion as to how closely Jewish norms could be tied to Israel’s actions in war, which this past summer included having killed many civilians apparently not involved in combat during Operation Protective Edge. The trail leads from the IDF Code of Ethics all the way back through Jewish history to Tanakh.

“The IDF serviceman will take into account, in every practical context, not only the proper concern for human life, but also the influence his actions may have on the physical well-being and spiritual integrity and dignity of others,” statesRuach Tzahal, the Code of Ethics of the IDF, which new soldiers study in detail.

“The purpose of the IDF is to protect the existence of the State of Israel, its independence, and the security of its citizens and residents.”

So the code requires soldiers to do their best to protect human life, and it also is in consonance with Jewish laws that clearly support killing in the case of self-defense. In fact, the Torah commands Israel to wage war against adversaries.

According to Judaic Studies teacher Rabbi Ari Schwarzberg, none of this, however, can really be considered “halachic” – firmly based in Jewish law. The problem is that there is no real halacha of war. Halacha was codified during 2,000 years when Israel was stateless. There’s no tractate about war the way there is, for example, about marriage, Shabbat or kashrut.

“It’s not easy to extract ethics of modern warfare from Jewish literature,” said Rabbi Schwarzberg, who worked with Jewish History Teacher Jason Feld last year to come up with a curriculum on the topic, which was taught to last year’s juniors.

“There’s ample discussion about war in Jewish literature,” Rabbi Schwarzberg said, “but it doesn’t necessarily parallel with the scenarios that the contemporary state of Israel faces.”

Issues that have surfaced since the founding of the modern state, he said, are being studied by rabbis, scholars and institutions now.

“These are issues that only surfaced in ancient times and then again in the last 60 years,” Rabbi Schwarzberg said. “It’s been a project that people are working on now — they’re grasping at traditional sources and seriously thinking about Jewish ethics of war, but almost all agree that the source material is scant.”

Rabbi Yosef Kanefsky of Bnai David-Judea Congregation, however, says that halacha is absolutely applicable to the situation today.

“The most relevant piece of halachic consideration is the law of the siege,” said Rabbi Kanefsky in an interview.

“The halacha requires that when a Jewish army lays siege, that they leave one side open so that anyone who wants to flee can flee — the reason being that in the state of warfare, anyone who wants to not be involved has to have the opportunity to get out and to escape the fighting.

“The underlying idea is that the halacha recognizes that there are people who are caught in the situation and they are not simply fair game.”

“In Gaza, there was no possibility of this,” he continued, adding that this did not release Israel from its obligation. That is how the IDF came to create military plans protecting civilians.

“The IDF drew up military plans and actions that made sure that civilians are not attacked,” he said, “and civilian deaths that are inevitable are weighed heavily against the strategic value of the military target. This is known as the doctrine of proportionality.”

Some other examples of halachic principles involving war are described below. But Mr. Feld said he thought they were off the point.

Mr. Feld said he didn’t think it was appropriate for anyone to justify the killing of civilians with religious principles – especially the IDF. Rather, he said, the force has taken blame and expressed profound regret.

RIGHT TO RETALIATE. Devarim Chapter 20, verse 12, states: “And if it will make no peace with thee, but will make war against thee, then thou shalt besiege it.”

The Torah here makes a clear distinction between war and murder, which would be forbidden under the Sixth Commandment. Because this is in the context of self-defense, there would be no violation of lo tirzach.

This is the most basic justification for Operation Protective Edge, which began as a response to a sudden uptick in rocket fire from the Gaza strip into towns of Israel’s south.

~ MILCHAMET MITZVAH, THE “OBLIGATORY” WAR: In Hilkhot Melachim 5:1-2, Rambam says a king can initiate a milchemet mitzvah, or obligatory war, either against one of the seven Canaanite nations – now considered extinct — against Amalek: or in self-defense.

Josh Horwatt, Shalhevet’s Director of Student Support and a former member of the IDF’s Givati Brigade, remembered thinking about Jewish law often during his service.

“Although there are many ideas and halachot about war, one of the most powerful and enduring is quoted in Rambam’sHilchot Melachim,” said Mr. Horwatt.

“The Kohen [priest] is to address the soldiers who are girded and ready for war. He says to them — and I am summarizing here — that they should expel thoughts of their homes and families and strengthen their hearts for the battle ahead so that their fear does not overcome them.

“I think it at the same time inspiring and heart-breaking, showing the intense emotions that all soldiers feel.”

~ ACCIDENTAL KILLING IN WAR. In the summer’s conflict in Gaza, the IDF made cell-phone calls, dropped leaflets and dropped small noise-making explosives so residents would know they should evacuate.

“Destruction of the infrastructure is a question that really goes into expertise of military personnel,” said Rabbi Kanefsky. “Halachists cannot make decisions when it comes to military. There are other people whose jobs it is to figure out which actions are going to best achieve defending the country.

“If it is the case that destroying infrastructure would cause Hamas to stop, it is okay,” he continued. “On the other hand, if destroying infrastructure was simply gratuitous punishment to be inflicted on a population, this would be a violation ofhalacha and of IDF rules of operation.”

~ KILLING TO PREVENT DEATH OR MURDER. Halacha defends the right to murder when being attacked or to prevent another murder. Sanhedrin 73a defines permissible behavior toward the rodef, which literally translates to chaser, or pursuer. Killing a rodef in most simple terms constitutes one of two situations: self-defense murder of one who intends to kill you, or killing someone who is trying to murder a third party.

Some believe this law does not apply because a rodef must be an individual, not a country. But the underlying principle seems applicable to those who are fighting.

“Jewish law recognizes many different kinds of wars and condones them,” said Josh Horwatt. “There is a category of war that is purely aggressive and exists to expand Israel’s borders – that is a milchemat reshut, meaning a voluntary war.”

“A milchemat mitzvah is a war fought to defend Israel from its enemies or to destroy one of our sworn enemies. The Jewish people have a long history of fighting. We were mountain warriors and tactical innovators. I don’t believe Judaism restricted our ability to fight, however it may have informed the values we practiced in battle – this I strongly believe.”

Everyone agreed that Judaism does not condone the killing of innocent civilians.

“No matter where you stand on the political or halachic spectrum, there is no doubt that death of Gazan civilians is an awful tragedy of war,” said Rabbi Schwarzberg. “Our tradition teaches us that we should not even rejoice at the downfall of our enemies, which should, at the very least, caution us about how we feel about the unfortunate consequences of war.”

And Rabbi Kanefsky added that supporting the state of Israel does not mean approving of everything it does, in war or otherwise.

“I think that one of the things that halacha always requires is that we take a step back and review what we have done in terms of our halachic and ethical norms,” he said.

“One of the most anti-halacha and anti-Jewish things we could do is to assume that everything that Israel does is right because Israel does it. The whole spirit of teshuvah, repentance, is that we never trust ourselves. We always have to look back and review and assess. That is core to what it means to be a halachic Jew.”

Related: A Summer Defined by War

Related: Summer of War: For Arab teens, a similar summer but with more death

Related: Summer of War: Hollywood, too, was divided

Related: A view from Israel: Who am I, who are we?

Related: A view from Israel, Part 2: Safety guilt

Related: A view from Israel, Part 3: Surreality

Related: In Israel’s north, staying safe means staying home for 250 underprivileged children

This story, together with its related coverage, won 2nd Place, Boris Smolar Award for Excellence in Enterprise and Investigative Reporting of the 2015 Simon J. Rockower Awards, sponsored by the American Jewish Press Association.