Lively Town Hall debate explores whether girls should be allowed to wear tefillin at school

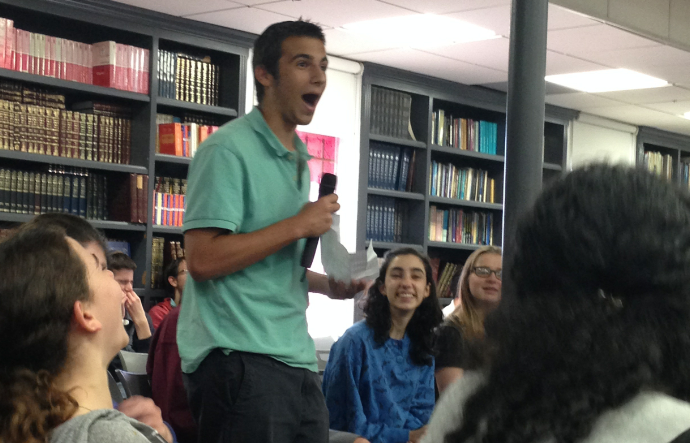

EVIDENCE: Junior Mati Hurwitz opened the debate with things he learned in Judaic Studies classes.

November 16, 2013

Should Shalhevet allow women to wrap tefillin and wear tallit during Shacharit?

This question began floating around Shalhevet on Oct. 25, when Rabbi Ari Segal, Head of School, put it into his weekly e-mail, “From the Virtual Desk of Rabbi Ari Segal.”

“A prospective student has asked me if she would be allowed to wear a tallit and tefillin during Shacharit if she were to enroll in the school,” Rabbi Segal wrote, referring to the prayer shawl and phylacteries worn by males during morning prayers.

The result, Rabbi Segal said, was a no-win situation.

“If I say yes, then I am certain there will be current and prospective families who feel the school is being too liberal,” his e-mail continued. “If I say no, I will have families who feel the school is not permitting an allowed mitzvah and is therefore being too closed-minded.”

A week later on Oct. 31, the topic was chosen by the Agenda Committee for what turned out to be a very intense, contested and yet polite Town Hall. It was announced a few days ahead, generating discussion in advance.

Being excited for this Town Hall, some even prepared arguments in advance. One of them was junior Mati Hurwitz, who turned out to be the first speaker called on by Agenda Chair Hannah-Leeba Ellenhorn.

Standing with a small piece of paper on which he’d scribbled major points, Mati outlined a range of commentaries that surround the idea of a woman wrapping tefillin — the small wooden boxes and leather straps containing the Shema, which boys wear during morning prayers in observance of the commandment, “You shall bind them as a sign upon your hand, and they shall for a reminder between your eyes.”

Mati gave two main halachic arguments – both, he noted, from the Shalhevet curriculum. The first, from 11th Grade Talmud class, was the Rambam’s statement that women can don tzitzit or blow shofar but without a bracha, or blessing – that is, it’s not commanded for them, so they can’t bless God for commanding them to do it.

Rambam, he continued, says ein memichin b’yadan — we don’t prevent it — Mati reported. He interpreted that to mean that while the rabbis don’t say to forbid it, they also do not embrace it. This general concept would also apply to other mitzvot of that sort, like tefillin.

Thus, since women do not generally wear tefillin, Mati said, it would create a tircha d’tzibura — a disturbance to the community, something which is halachically forbidden — if they did. Shalhevet should therefore not forbid girls from wearing tefillin, but the girls themselves shouldn’t do so because it will inflict distress upon the community, Mati told Town Hall.

His second argument came from the 11th Grade Tanakh and 10th Grade Talmud courses. Studying the sin of the Golden Calf, he said, they learned that Ibn Ezra believes the Jews were punished for not serving God the way He had commanded them to. Since tefillin as a mitzvah is designed in the Torah for men, women’s following it would be serving God in a different, and thus perhaps sinful, way.

“I don’t mean to interpret God’s words — it would be blasphemous to do so,” Mati said, “but I have sufficient halachic evidence to back up my philosophy and formulate my opinion.”

He ended off his second argument by connecting the “not commanded” point to a concept he knows of, called gadol hametzuveh v’oseh mi’sheaino metzuveh v’oseh — literally, that one who is commanded in a mitzvah is greater (in doing that mitzvah) than one not commanded. That means women aren’t getting more “mitzvah points” with God by wearing tefillin, he said, so they are not gaining anything by doing it, at least halachically.

Mati finished off his speech with a personal view.

“I personally don’t mind if a woman wraps tefillin,” Mati said. “Just do it at home.”

This was greeted with a lot clapping and laughing from around the room. It was hard to tell whether all the clapping was supportive, since many people clap after every Town Hall comment whether they agree or not.

A wide-ranging discussion followed, as speakers, mostly students, responded to Mati’s points with a variety of other arguments. Many students said Shalhevet is a part of the Modern Orthodox movement and cannot decide rules and guidelines on its own. Students said that if Shalhevet wants to stay Modern Orthodox, it should not let this girl wrap Tefillin.

Sophomore Jonah Gill responded to these claims.

“Modern Orthodoxy is a phrase coined 40 to 50 years ago,” said Jonah. “It is not like we have been practicing it for hundreds of years. We can fix it and change it.”

Others referred to the standing of minhag – literally, custom – in Jewish law, a concept studied in 9th,10th and 11th grade classes.

“We learned about minhag and the power of it and how it can be distinguished from opinion,” said junior Margo Feuer. “The minhag is for women not to wrap tefillin, so why would that be changed?”

There are some Gemaras that say if a minhag is widely practiced and followed, then it can establish halachic status, she added.

Some of the female students said that women want to wrap tefillin to feel closer to God or Judaism. Junior Yosef Nemanpour was one of several boys who responded by quoting the belief that women are already closer to God than men are and that men actually wrap tefillin in order attain the same high level as women.

Other boys said that seeing a women wrap tefillin and wear a tallit, or prayer shawl, would actually hinder their davening experience. Senior Josh Einalhori was one.

“It is not my custom for a woman to wrap tefillin,” said Josh. “If a woman was wrapping tefillin, I would not leave, but I would feel uncomfortable.”

Junior Sigal Spitzer responded that since halacha doesn’t say women can’t do it, it’s wrong to make a community decision based on what other people do or don’t want to see.

Around that time, Hannah-Leeba called on English chair Ms. Melanie Berkey, who noted that many more boys than girls had been speaking.

“I just want to say that what affects women and defines women has been defined by all the men in this room,” Ms. Berkey said. After that, more girls started to stand up and talk.

Senior Kaili Finn was the first.

“For all the guys that say it has no meaning (to women), you need to stop because you don’t know what they feel,” said Kaili. “Girls should be able to wear tefillin on their own time and Shalhevet needs to cater to what the community needs.”

It was the first time in the discussion that a Shalhevet girl had taken this stance.

Senior Benny Balazs replied that he supported girls wearing tallit and tefillin, but that Shalhevet should not allow it because the girl might be ostracized.

Art Teacher Roen Salem responded that Shalhevet had increased girls’ opportunities in the past, for example letting girls sing solos starting just last year.

“There always has to be one person to lead,” said Ms. Salem. “This is the beauty of our school… We allow women to sing in front of men. Now we are thinking about this and I don’t think we should be closed-minded.”

Many students were wondering why more teachers didn’t speak. It turned out that Principal Reb Noam Weissman had sent out an email to the faculty prior to Town Hall asking them not to talk, though not all teachers had seen it.

“I think that since the teachers are more educated than the students, it would have been nice to hear their thoughts, as opposed to the students repeating their own comments,” said sophomore Kian Marghzar.

But Rabbi Segal was glad to have heard mostly the students speak.

“Reb Noam suggested to all Judaic faculty that we allow the students to speak,” Rabbi Segal told The Boiling Point via e-mail later. “I think he was hoping that this would allow to students to really express their thoughts… I think he was right.”

As for his final decision, Rabbi Segal said he would announce it Thursday evening – also by e-mail.

Related story: Girls will not wear tefillin at Shalhevet, Rabbi Segal decides

Related story: Mother and daughter who sparked tefillin debate respond to Rabbi Segal’s decision

Related story: Some variety in how Modern Orthodox schools see tefillin issue

This story is part of coverage that won 2nd prize in the Boris Smolar Award for Excellence in Enterprise or Investigative Reporting of the 2014 Simon J. Rockower Awards, given by the American Jewish Press Association, in the category of newspapers with under 15,000 circulation. It also won the Grand Prize in Jewish Scholastic Journalism from the Jewish Scholastic Press Association.

Mod Ox • Aug 23, 2017 at 8:28 am

Tefillin are not “wooden boxes”… They are made of leather from a kosher animal.