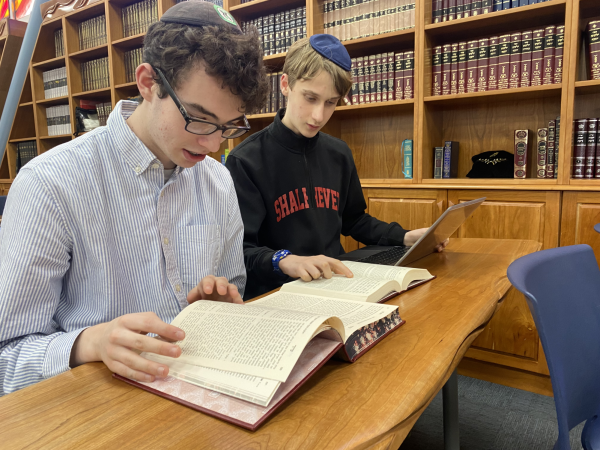

Boiling Point staffers are reporting from the senior trip to Poland and Israel.

We made it.

After one of the most exhausting weeks of my life, I have finally arrived in Israel. By no means was this an easy journey. A few days ago in Majdanek, our group actually sat down inside a crematorium singing. It was eerie and uncomfortable, but hearing Jews singing and dancing to those same songs last night at the Kotel was surreal.

On our last day in Warsaw, we happened to see the unveiling of a a unique hedge stone. A woman named Blima died during the Nazi occupation under a fake Christian name. She was therefore buried in a Christian cemetery, and her headstone there had been defaced over the past 60 years. Last November, her family finally succeeded in moving her body to a Jewish cemetery, and a few days ago, they unveiled her headstone in front of our group.

When we finally landed in Israel, we were told our bus had brokn down and we would be taking taxis to Jerusalem. Funny, we said — this wasn’t the first time our bus broke on this trip. Days before, we ended up in the middle of the forest in Poland, and half our grade had to push our enormous bus past some mud.

This time, though, it was on purpose. Our chaperones ended up putting us in jeeps, telling us they were cheaper than taxis. In reality, they’d been arranged so we could drive in early morning down the bumpy — and famous — Burma Road to Jerusalem. We were running on about three hours of sleep, but it was amazing to see a road that had been created virtually overnight to supply surrounded Israeli fighters during the siege of Jerusalem in May of 1948. The views of Israel were beautiful, and the large breakfast served to us in the middle of the road certainly excited our group.

Last night, we davened at the Kotel, the perfect contrast to last week. We, as a nation, have gone from tragedy to freedom.

Auschwitz vs. Lublin: Wrapped in the Flag

By Kalil Eden, Opinion Editor

First it was March of the Living and then it was Shalhevet. It’s become a tradition, and it happened on our trip too — chaperones bring Israeli flags, or students bring their own … and it’s not uncommon to see them worn cape style through Auschwitz, especially walking down the train tracks to the crematorium, and also while praying at the gate.

Why is it that the Israeli flag should be chosen to say, “We’re still here”?

Israel does not represent everything that the Holocaust tried to destroy. True, Jewish culture, peoplehood, and religion often overlap with Israel, but these are all categorically separate spheres.

Israel doesn’t grant citizenship to many Jews whom the Holocaust would have threatened. Take, for example, Conservative and Reform converts. Conversely, “Israel” has everything to do with things we don’t think of as remotely Jewish: might clubs in Tel Aviv, for example.

The next thing is that it distracts and loses your audience (and yes, you have one). Europeans, even if they hate the Nazis and their crimes, are split on Israel. Non-Jewish onlookers are put into an awkard conflict. When I think back on some of the confused looks we got at the Auschwitz museum, I have to say: no wonder.

Kalil, isn’t that a little pedantic? We don’t have to be so exact. I’m wearing it for me, not for some twisted onlookers. The flag comforts me.

And I forgot my windbreaker on the bus. But there are some things more important than personal comfort, even in the hell of Auschwitz. The symbols we adopt have tangible effects on the world around us and therefore carry some responsibilities.

Lastly, I hate to do this, but I have to question the motives behind this fashion. Yesterday was Yom HaAtzmaut; did nearly as many people (or anyone) want to wear the flag around Lublin’s town center? Why is it that we stuff the flags into the overhead bins when we get on the bus instead of folding them up properly? Why is it that no one seems to know the words to HaTikvah? “Wrapping yourself in the flag” is an expression for a reason — it’s showy and conveniently dramatic. But it seems like less of a statement and more of a photo op.

Wolbrum Forest: Tangible and surreal

By Rose Bern, Senior Staff Writer

April 15: As my classmates and I trudged through the Wolbrom Forest, I internally complained about the snow seeping through my combat boots. And then I heard the guide explain that 800 children were murdered on the very spot where I was standing. I could no longer feel the uncomfortable dampness in my shoes.

“Forced to dig their own graves,” he said. “Some were buried alive while others were shot and then thrown into this mass grave.”

Children, the pinnacle of everything innocent in this world, their lives and futures stolen from them. Almost worse than that, I grappled with the fact that this story is not an anomaly of the Holocaust, this was a commonality.

Children, the pinnacle of everything innocent in this world, their lives and futures stolen from them. Almost worse than that, I grappled with the fact that this story is not an anomaly of the Holocaust, this was a commonality.

Today in Auschwitz, I saw hair. This hair belonged to the thousands of women who were transported there. Every strand of hair was attached to a sentient person at one time. A human being with a name, her own quirks, and aspirations.

That affected me more than walking through the death camps. The camps are surreal; one simply cannot believe the horrors we know about ever occurred there.

But seeing the hair — a visual image that will be forever burned in my mind — was tangible, different. I looked down at my hair and looked at their hair. It’s arbitrary that my hair was in front of the display case rather than behind it. I was born in the right place at the right time. They were inauspiciously not.

Walking away from the past few days, my heart is shattered. I don’t know how to extrapolate anything positive from this experience. But I know I owe it to those who were murdered to not be passively sad.

Coming on this trip has compelled me to realize the importance of the legacy of Judaism I must carry on. It is no longer a burden, it is a necessity.

I now fully comprehend the importance of my Jewish identity, and know that the Holocaust will never define my people. Rather, an undying dedication to our faith and culture have enabled us to continue fulfilling its legacy, even after tragedy, on this side of the glass.

April 13 – Lodz: Trying to humanize the scene

Colleen Bazak, Co-Editor-in-Chief

For me at least, it’s been difficult to process what we’ve experienced in the past 48 hours.

At the Radegest transport station, our group of fewer than 50 sat for a few minutes in one of the trains where over 100 Jews were once crowded inside for days at a time. Although we were sitting inside such tangible proof of the Holocaust, I kept searching for something else. A few of us started inspecting the walls. We wanted to find anything, like an engraved initial or even tally marks – something to humanize the scene.

We didn’t, and it continues to be impossible to understand the frame of mind of those who were killed. We’ve seen the utensils they left behind, and even their bones in Chelmno, but we can’t know what they were thinking when they reached that forest in Chelmno; we can’t feel their fear or hear their thoughts. All we see is a large mass grave surrounded by a daunting forest on all sides.

I also expected to be able to picture what happened. But even as we were finding human bones on the ground, I couldn’t fathom it. Despite all the proof around me, I couldn’t and can’t imagine thousands of Jews just being killed, buried, and burned. I don’t want to believe it. I can’t help but hope that maybe the bones we were holding were actually rocks.

Today, on Shabbat, we took a walking tour of Lodz, and, I also realized something else — that I will never understand the mindset of the Nazis, and those who helped them do what they did. The Poland we are walking through may be depressing and dreary, but the atmosphere of the Holocaust doesn’t dominate it. Out and about, many of us were struck by the normal demeanor of the Polish people walking. Some students couldn’t help but wonder whether these people we are seeing have ancestors who killed Jews in the camps. But to me, it seemed impossible that people who appear just like us could have committed these crimes. In my mind, the people who shoved Jews in trains and then gased them couldn’t be human.

I’m realizing that the most difficult part of this trip, for me, will be coming to terms with the mindset of both the Jews and Nazis at the time. However, I’ll have to do that without really understanding it — because that understanding is the one thing this trip, or any story or proof in the world, will never be able to provide me.

April 12, Warsaw, Lodz and Chelmno: Why we’re here

Kalil Eden, Opinion Editor

What on earth am I doing in Poland?

Standing in the Warsaw Chopin International Airport, my presence seemed as unnatural as the flight over.

Man was not meant to fly, and Jews were not meant to travel in Poland.

I found myself suspiciously wondering where and how an elderly cashier spent the years from 1939 to ‘45, and who really would have owned various buildings if land hadn’t been redistributed after every regime change, and whether the graffiti, unbeknownst to foreigners like me, had illegible, anti-semitic undertones.

It was extremely uncomfortable, not only for me, but I imagine for the innocent commuters I could not help but stare at.

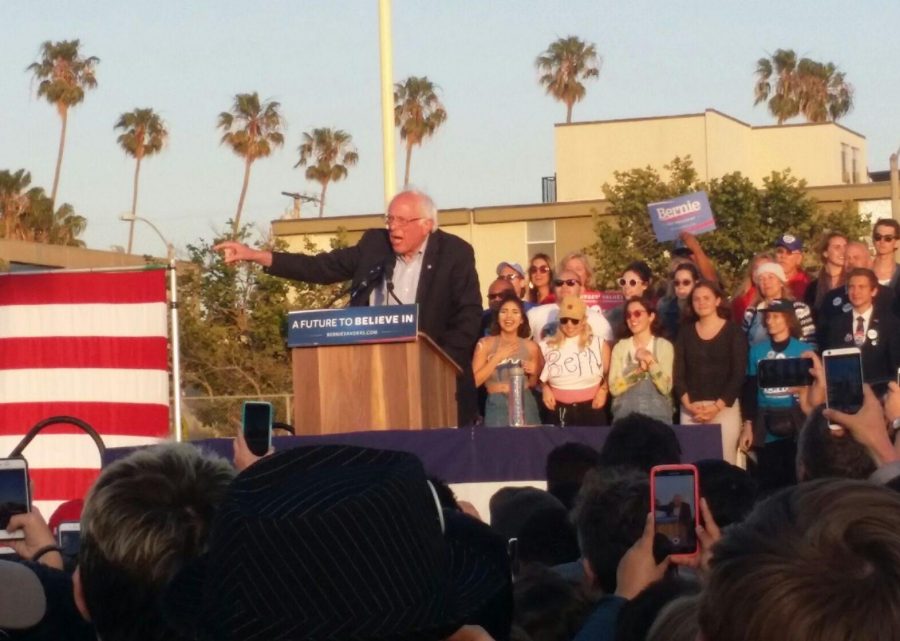

I know I’m not alone here. What we’re doing here is controversial at best. A lot of Jews can’t bring themselves to visit, either because it’s too emotionally difficult, or for more symbolic reasons, for instance, because it means giving money to the country that hosted so many death-camps. Two members of our class, even, are skipping this week in Poland and meeting the group in Israel.

I’m going to ignore the “experience” aspect of the trip (I imagine that’s the first thing everyone thinks about when they weigh the pros and cons of going) and just lay down some data: Poland has anywhere from 30,000 to 55,000 Jewish residents who, for whatever reasons, don’t share our discomfort. Warsaw isn’t exactly the New York of Eastern Europe, but that’s nothing to sneeze at.

By refusing to visit, it effectively quarantines a historically (if not numerically) important Jewish community. Honestly, they’re the ones that notice our absence, not the Polish Ministry of Tourism, or whoever.

Not that you have to come on this trip, or see Poland with your high school, but to refuse point-blank isn’t an individual statement; it’s cutting off a limb.